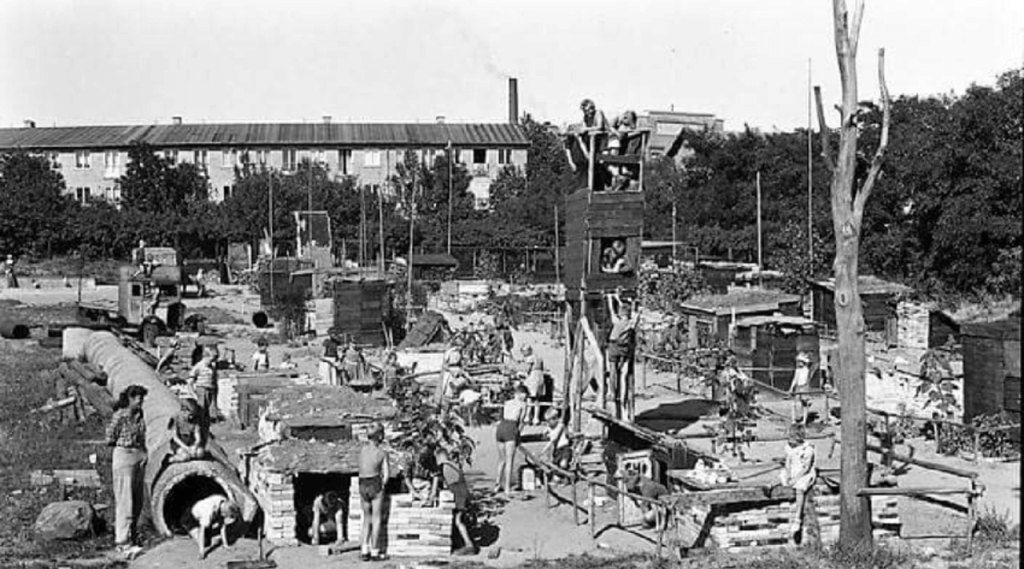

In 1943, amidst a backdrop of growing Danish resistance to Nazi occupation, a Skrammellegepladsen (Junk Playground) opened to the children of Emdrup, Copenhagen. A collaboration between Danish landscape architect Carl Theodor Sørensen and John (Jonas) Bertelsen, the site was minimally adapted to replicate elements of rural Denmark: “the beach, the meadow, and the grove”. Many cite this as the first planned adventure playground.

Three years later, in 1946, English landscape architect and children’s rights advocate Lady Allen of Hurtwood visited Emdrup. Upon her return to England, Lady Allen propagated the idea of adventure playgrounds by posing the question “Why Not Use Our Bomb Sites Like This?” in an article of the same title in Picture Post magazine.

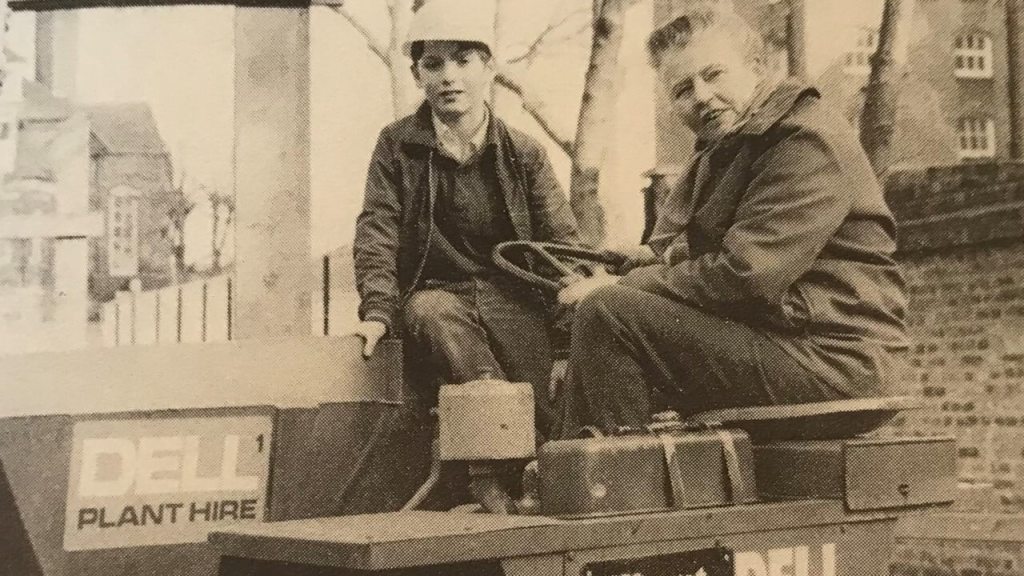

It would take nearly 40 years for the term “playworker” to emerge, but the roots of the profession are irremovably intertwined with the emergence and evolution of adventure playgrounds and the societal remembering of the importance of children’s play.

Despite this distinctly Britannic institute now being exported across the globe (in one form or another), its foundries, adventure playgrounds, are under threat. But to what extent?

Where to start

The first mapping exercise that this list relies on was conducted by Play England around 2007/2008. This effort supported the planning of the Play Pathfinder Project, which aimed to promote children’s play and improve the quality of playwork provision in England. Funded by the Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF), and managed by Play England, the project launched in 2008 and ran until 2011.

Some of the principles that underpinned the Play Pathfinder adventure playgrounds included providing the widest possible range of opportunities for children’s play, creating a shared flexible space that children feel has a sense of ‘magic’, and involving children and young people in creating and modifying the play space within a varied landscape. This would later be developed into a practice briefing entitled ‘Developing an adventure playground: the essential elements’, written by Mick Conway in 2009.

The most recent iteration, ‘Adventure Playgrounds: the essential elements‘, was published by Play England around 2012 – 2013. In it, an adventure playground is defined as:

“…a space dedicated solely to children’s play, where skilled playworkers enable and facilitate the ownership, development and design — physically, socially and culturally — by the children playing there.

It is enclosed by a boundary to signal that the space within is dedicated to children’s play and to enable and encourage activities not usually condoned in other spaces where children play, such as digging, making fires or building and demolishing dens and other constructions”

Below is a summary of the 12 “essential elements”:

- Staffed by skilled and appropriately qualified playworkers working to the Playwork Principles.

- Allowing for spontaneous, free expression of children’s drive to play.

- Opportunities to engage in the full range of play types as chosen by children.

- Exploration of physical, social, emotional, imaginary, symbolic, and sensory spaces.

- Free flow in giving and responding to “play cues” to ensure children can determine the content and intent of their play.

- Creating a shared flexible space that children feel has a sense of “magic”.

- A rich play environment that continually changes and evolves, where children can play all year round in all weathers.

- The active involvement of children and young people in creating and modifying the play space, within a varied landscape.

- The playground is at the heart of the community.

- It is designed to be accessible to all children, and is based on inclusive practice so that disabled, non-disabled children, and children from minority communities are welcomed and enabled to play together.

- Entry to playground is free of charge, children are free to come and go, and free to choose how they spend their time when there.

- Risk management is based on the principle of risk-benefit assessment, balancing the potential for harm against the benefits children gain from challenging themselves in their play.

As early as 2013, but more concertedly in 2017, Mick Conway independently brought together a group of volunteer playworkers and play advocates to update the original list. In just a decade since the original mapping exercise, it was becoming clear that “adventure playgrounds were becoming an endangered species in many areas”, according to Conway.

Almost five years later, in November 2021, Play England sought to further update the 2017 list and commissioned Lesli Godfrey to research the spread of adventure playgrounds in England. The goal was to update and expand existing records and to lay the groundwork for a network of adventure playgrounds. To accommodate contemporary adaptations to the delivery of playwork provision on adventure playgrounds, including the legacy of COVID-19 public health protection measures, the definition of “adventure playground” was adapted. This work was completed, and the ‘Play England Report into Adventure Playgrounds in England‘ was published in March 2022.

Then-Trustee of The Playwork Foundation, Jackie Boldon, approached Play England for the detailed list and proceeded to convene a voluntary working group to review its contents. Systematically, they updated the list based on what they knew on the ground and what they could discover through desk research. The mapping was also extended beyond England to the rest of Great Britain.

After much delay, the list has now being made available here. Our gratitude to Mick Conway, Play England, and Jackie Boldon for taking on this mammoth task. Credit also to existing repositories of adventure playground information, such as London Play‘s adventure playground directory.

Please help us keep this list current by emailing any corrections or updates to apn@playwork.foundation.